Southern Somebodies

01.06.23 > 27.08.23

The Gallery of Everything presents SOUTHERN SOMEBODIES, a curated response to, and visual expansion of SOULS GROWN DEEP LIKE THE RIVERS, formerly at the Royal Academy in London.

SOUTHERN SOMEBODIES features the work of over a dozen Black makers from the American south, each of whom has instigated an informal and instinctive personal practice.

The works in the exhibition aim to broaden our understanding of what constitutes a Black American vernacular, and to highlight the joy, invention and meaning within.

Artist names are listed below, click on any individual name to take you to the artist's page:

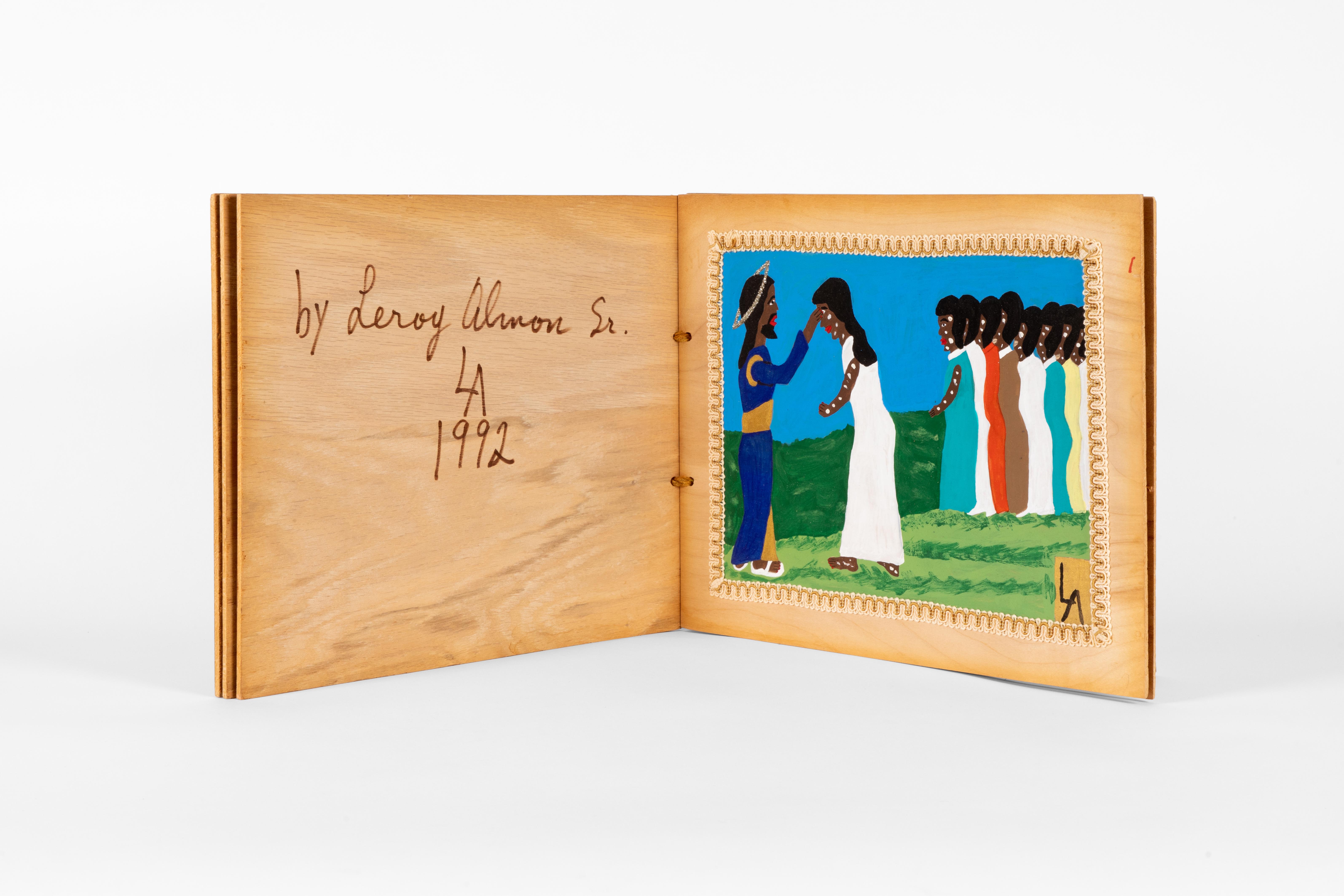

Leroy Almon

Zebedee Armstrong

Hawkins Bolden

David Butler

Freddie Brice

Richard Burnside

Vernon Burwell

William Dawson

Sam Doyle

Josephus Farmer

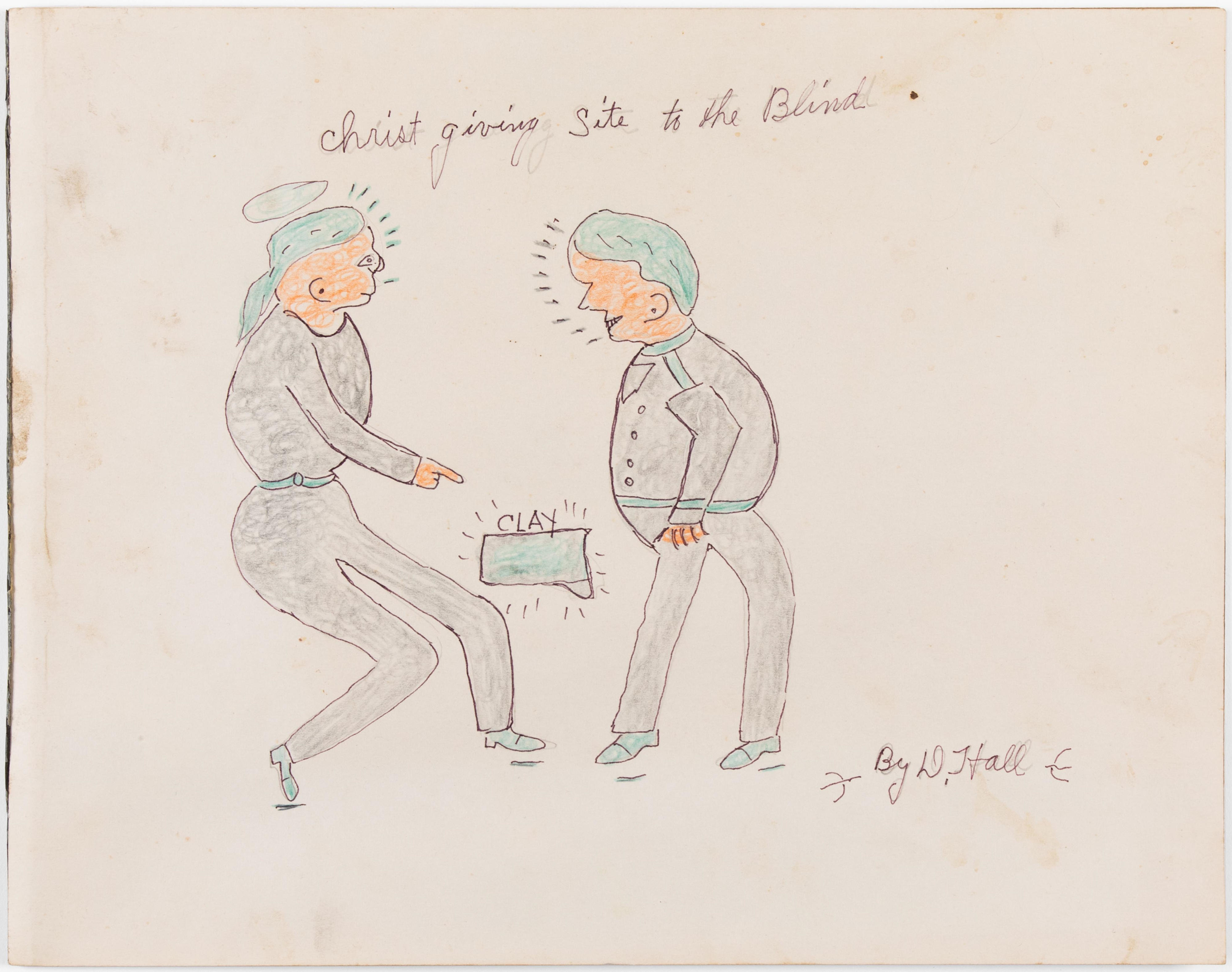

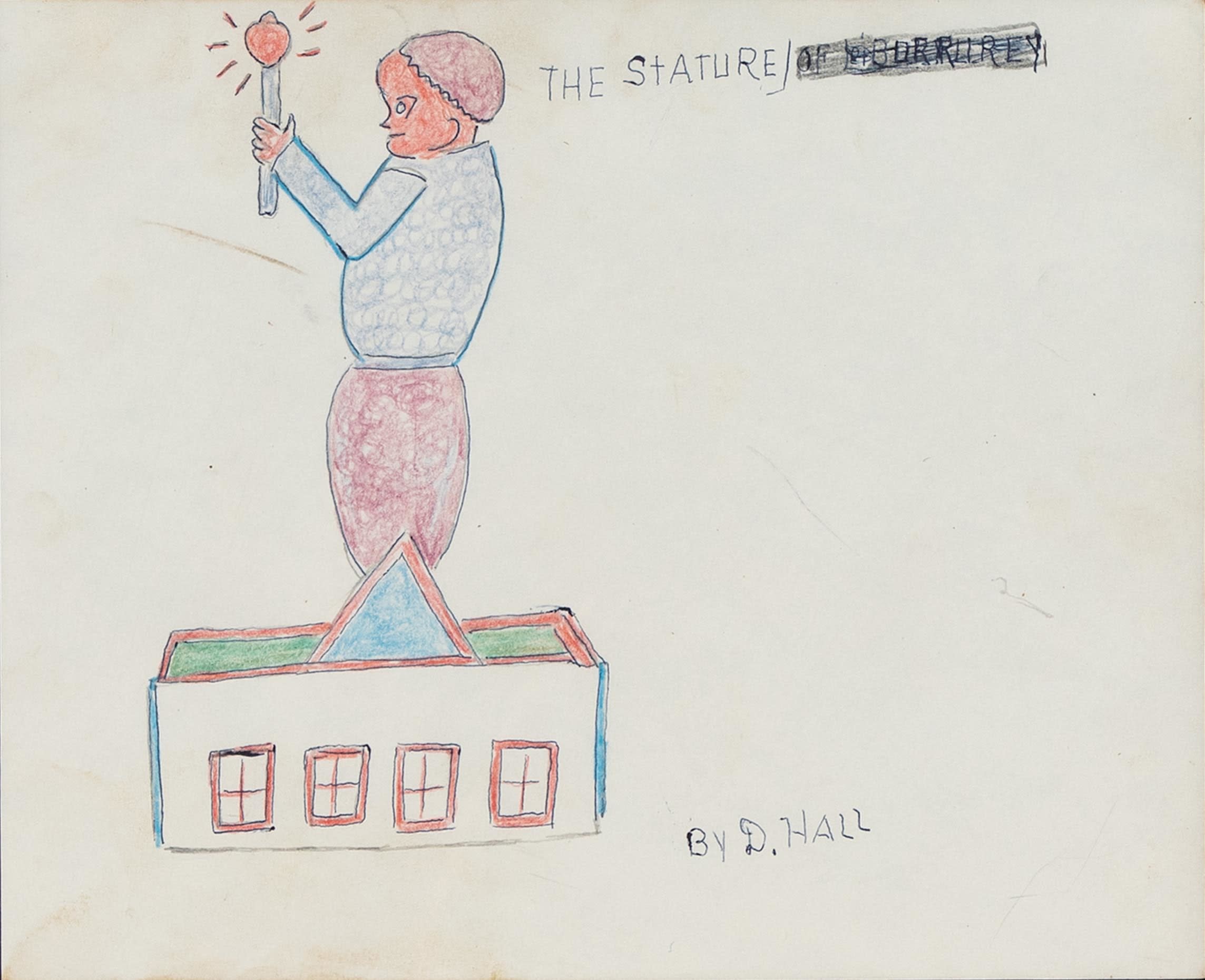

Dilmus Hall

Lonnie Holley

Rev JL Hunter

Charles Kinney

OW Pappy Kitchens

Willie Massey

JB Murray

Prophet Royal Robertson

JP Scott

Herbert Singleton

Henry Speller

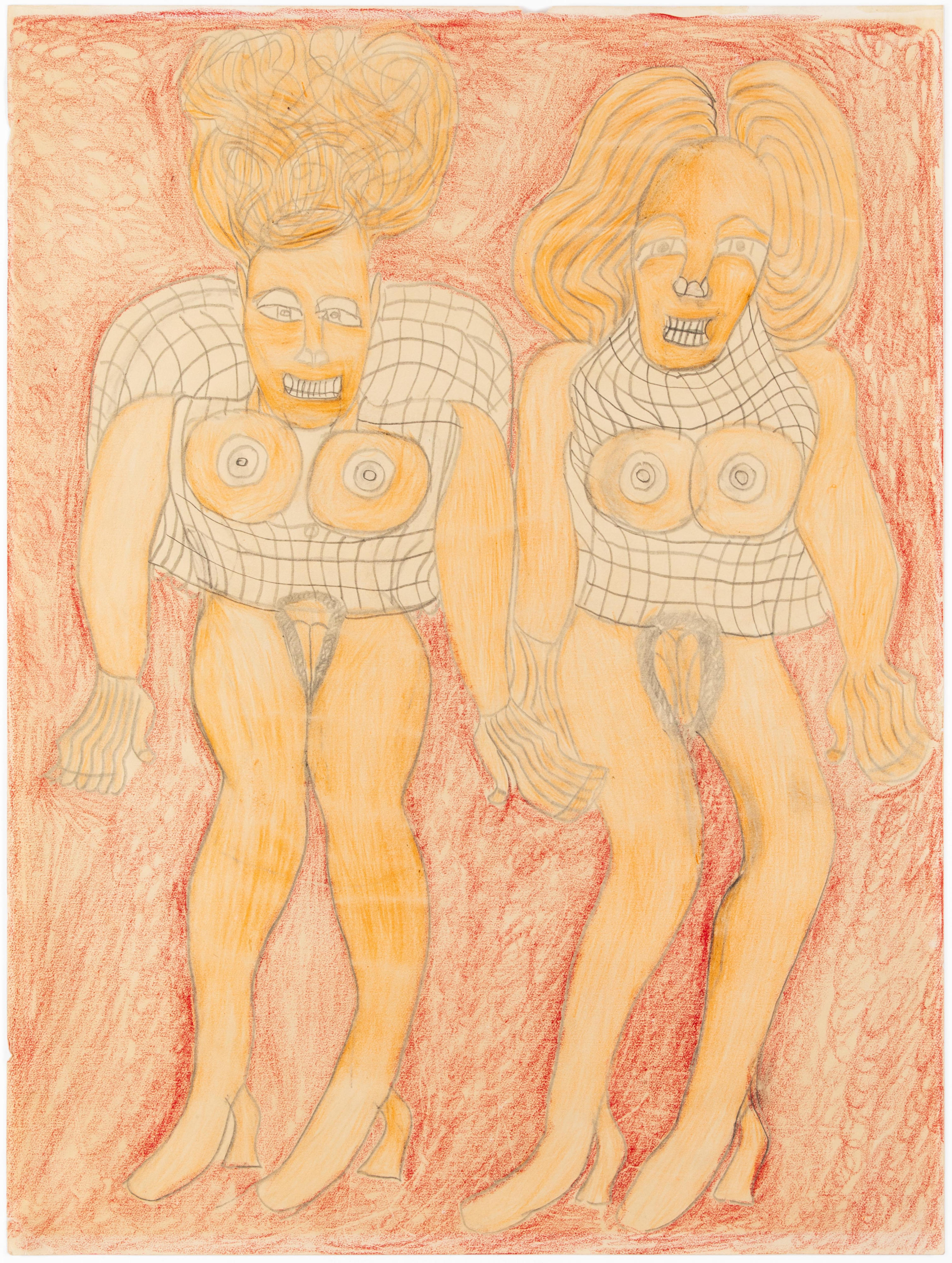

Dr Charles Smith

Mary T Smith

Jimmy Lee Sudduth

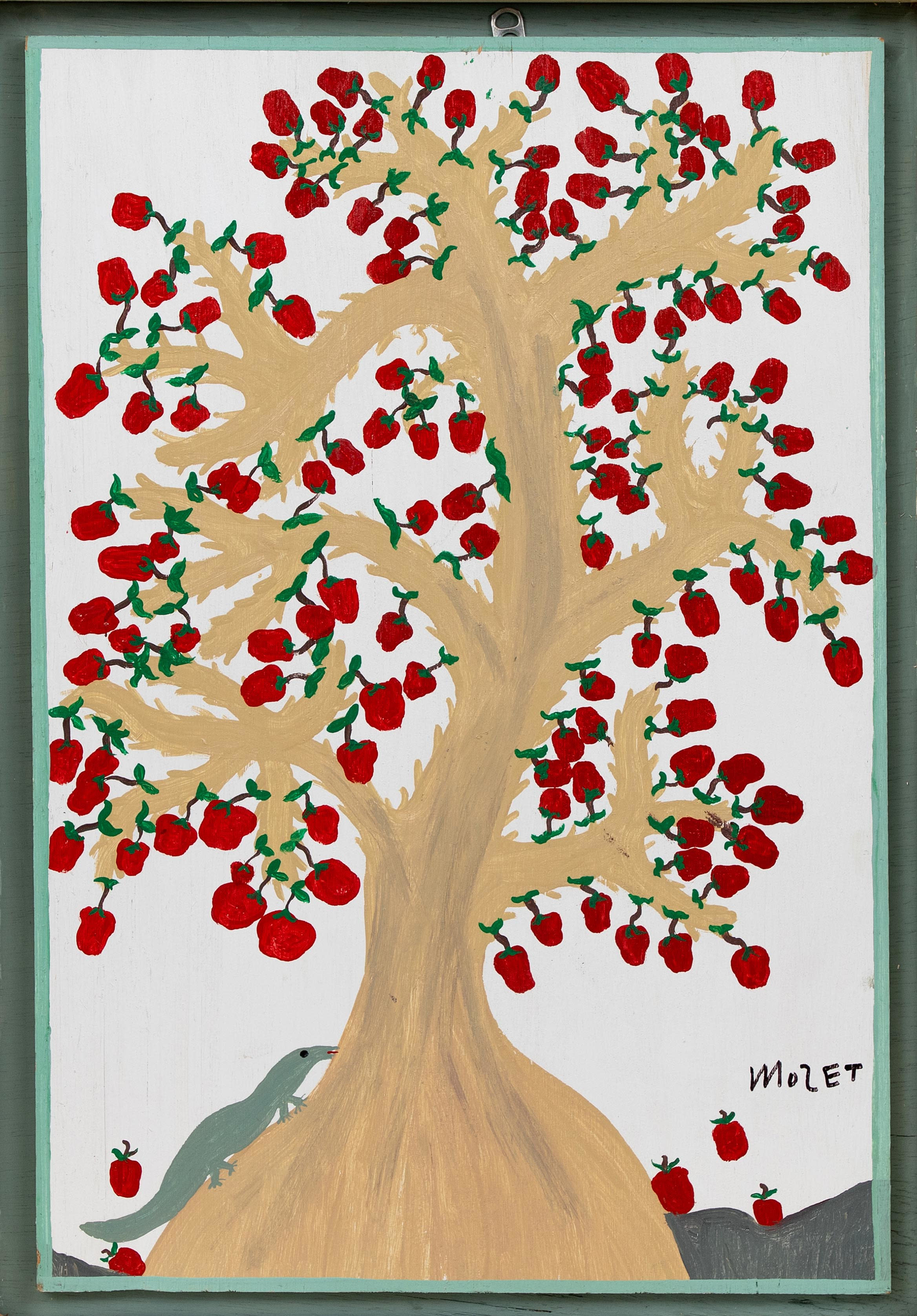

Mose Tolliver

George Williams

For available works, please contact the gallery.

What Are You Saying? And Why Are You Saying It?

It’s always been the role of the artist to transform raw materials into something new. But what happens when the materials to hand aren’t oil paints, marble, or art materials at all, but junk and cast-offs, rusted tin doors and ancient kitchen sinks?

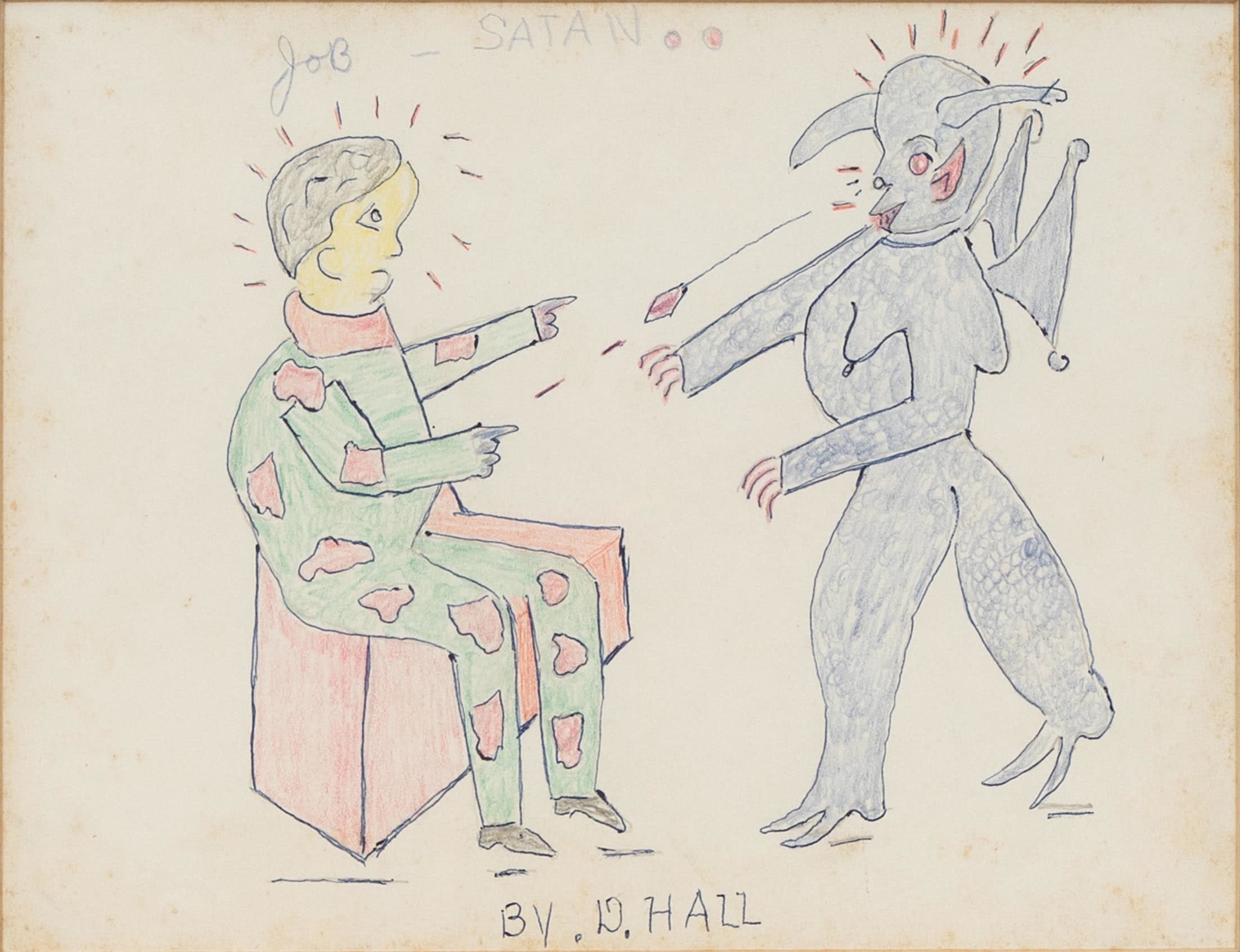

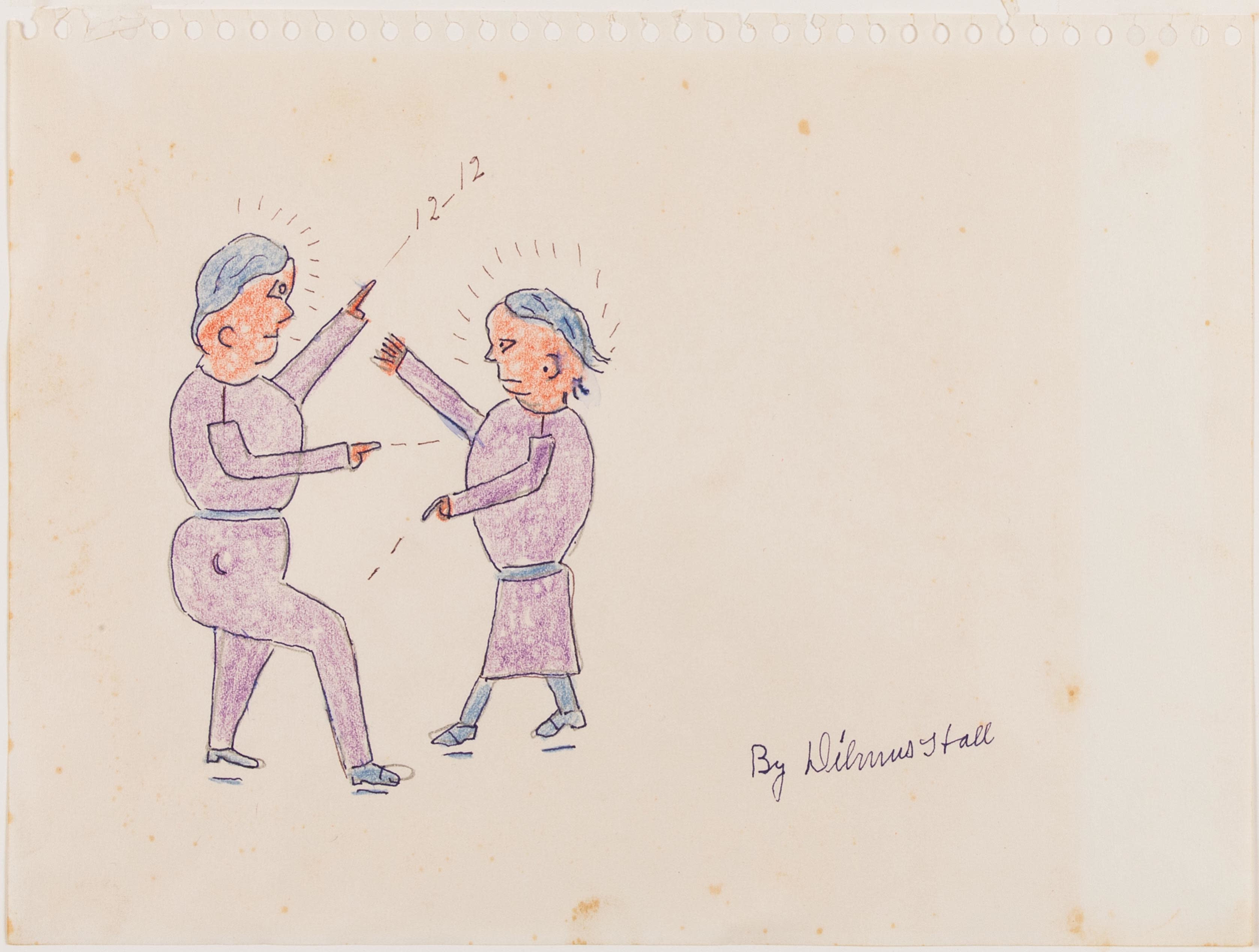

When I was a boy I thought about trains, and I’d take some bed rails and call it a track, recalled Henry Speller, of his childhood on a plantation in the Mississippi Delta. Tree roots, that’s what I started with, said Mose Tolliver, born in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1924. Dilmus Hall, from a farming community near Athens, Georgia, began by mixing flour with sweet gum from blazing trees on the family land.

Together, the 26 artists of the American South included in Southern Somebodies demonstrate with unusual clarity that the act of making is always also the art of making do. This isn’t just true of the materials they use. For these artists, who almost never had access to formal arts education, learning their craft was a process of experiment and bricolage, of piecing ideas together to forge a style all their own.

Take Prophet Royal Robertson. Born in 1930 in Louisiana, Robertson worked for a time as a sign-painter. He sent away for a correspondence art course, became a diligent student of sci-fi comic books and TV cartoons, architects’ drawings, adult magazines and, tying it all together, the Book of Revelation. He cobbled these disparate elements together into a profoundly idiosyncratic mythology: brash visions, realised with magic markers, tempera paint and glitter on poster board or wooden panels. God, driving a spaceship, informed him at the age of 14 that the end of days was nigh, or so he claimed in later life.

Or Hawkins Bolden, the relentless fabricator, who began making in 1965, nearly 40 years after a baseball accident left him blind. Bolden's scarecrows – metal objects punched with holes to keep birds away from his vegetable patch – blossomed to encompass all sorts of assemblages, from human figures to abstract forms, and made of everything from rusted appliances to leather belts. They speak of vivid interiority, of a compulsion to interpret and transmit the human form.

What can I, an arts writer with a traditional education, presume to glean from the brilliant fire-and-brimstone visions of a Black man who grew up in the Jim Crow South, yet clearly also suffered from complex mental health issues? Or from a maker whose visual impairment led him to deny art to any of his creations?

When seeing works of David Butler in a gallery space, it’s necessary to keep in mind that his sculptures were displayed in his own front yard. Butler, born in 1898 in Good Hope, Louisiana, combined tin, wood, bicycle parts and kitchen appliances to create his elaborate whirligigs, some adorned with sharp-toothed figures reminiscent of African ritual, some drawing on Christian biblical imagery.

Butler’s expansive displays of kinetic sculptures were part of a grand tradition in the American South: the yard show. Lonnie Holley’s vast Environment (as he called it) in Birmingham, Alabama, was another, combining paintings, sandstone carvings and scrap-metal. It was bulldozed to make way for an airport in 1997.

The young Robert Rauschenberg was profoundly influenced by these yard shows. Their influence is tangible in his celebrated Combines – which just goes to show that the line between the formal and the informal is fugitive. But there’s a danger, in looking at this work through the eyes of art world luminaries, of justifying their importance with recourse to the establishment, rather than on their own terms. It is a problem which recurs with every show, and indeed, an essay such as this.

In a number of ways, the issue is exemplified by the recent exhibition at the Royal Academy in London, where works from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation are on display. This project, started by the late William Arnett in the 1980s, promotes the work of (mainly Black) vernacular artists from the American South, and features several of the artists in Southern Somebodies. Yet there is also an implication that these artists have come of age by being welcomed into the hallowed halls of the world’s oldest art institution here in the United Kingdom.

It is the ambition of the present show at The Gallery of Everything to let the individuality of these makers come to the fore – to give scope and space to those who have been marginalised, even in an era committed to broadening the canon. To achieve this, it’s important to meet the artists halfway – to do the imaginative work of propelling oneself both into the world they found around them, and the world they sought to remake through their art.

Often, these overlap – as in the remarkable art of JP Scott. After dropping out of school in the sixth grade, Scott followed in his father’s footsteps and became a fisherman. Yet in his fifties, he began creating model boats and chapels out of scrap metal, unwanted fragments of fisherman’s netting, driftwood, Mardi Gras beads and whatever else came to hand, leaving them outside for weeks to weather.

Freddie Brice was another who sought inspiration from everyday environments and imagery. After a troubled childhood in Charleston, South Carolina, and a lifetime of manual labour, Brice started painting in an assisted East Coast studio. His predominantly monochrome paintings on plywood panels, with their careful graphic economy, were eventually noticed and brought to the fore by the New York art crowd, notably by Connie Butler, today the director of MoMA PS1.

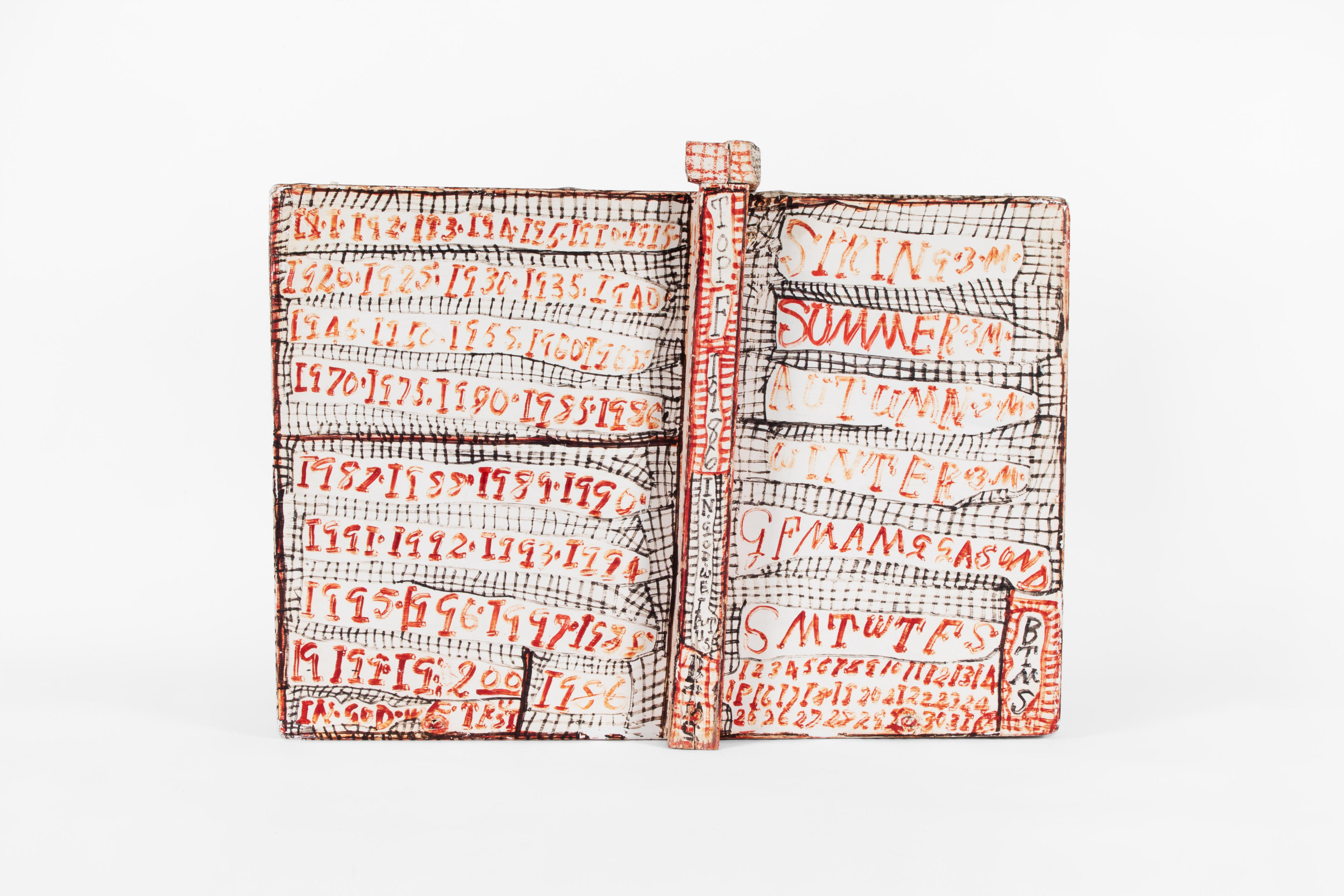

Zebedee Armstrong worked most of his life as a cotton picker in Thomson, Georgia. He was visited by an angel in 1972 who informed him that our time has gone to waste… judgment day will come soon. Over the course of the two decades that remained to him, Armstrong produced 1,500 calendars – with clocks and dials and intricate grids of numbers and text – to pinpoint the moment of Doomsday.

What does this tell us? Art, at root, is a means of communication. It’s an attempt to give shape to experience, rendering one’s personal understanding of the world intelligible to others (and perhaps, also, to oneself). And as with any communication, it helps to have a decent sense of where the other person is coming from – to understand why they’re saying what they’re saying.

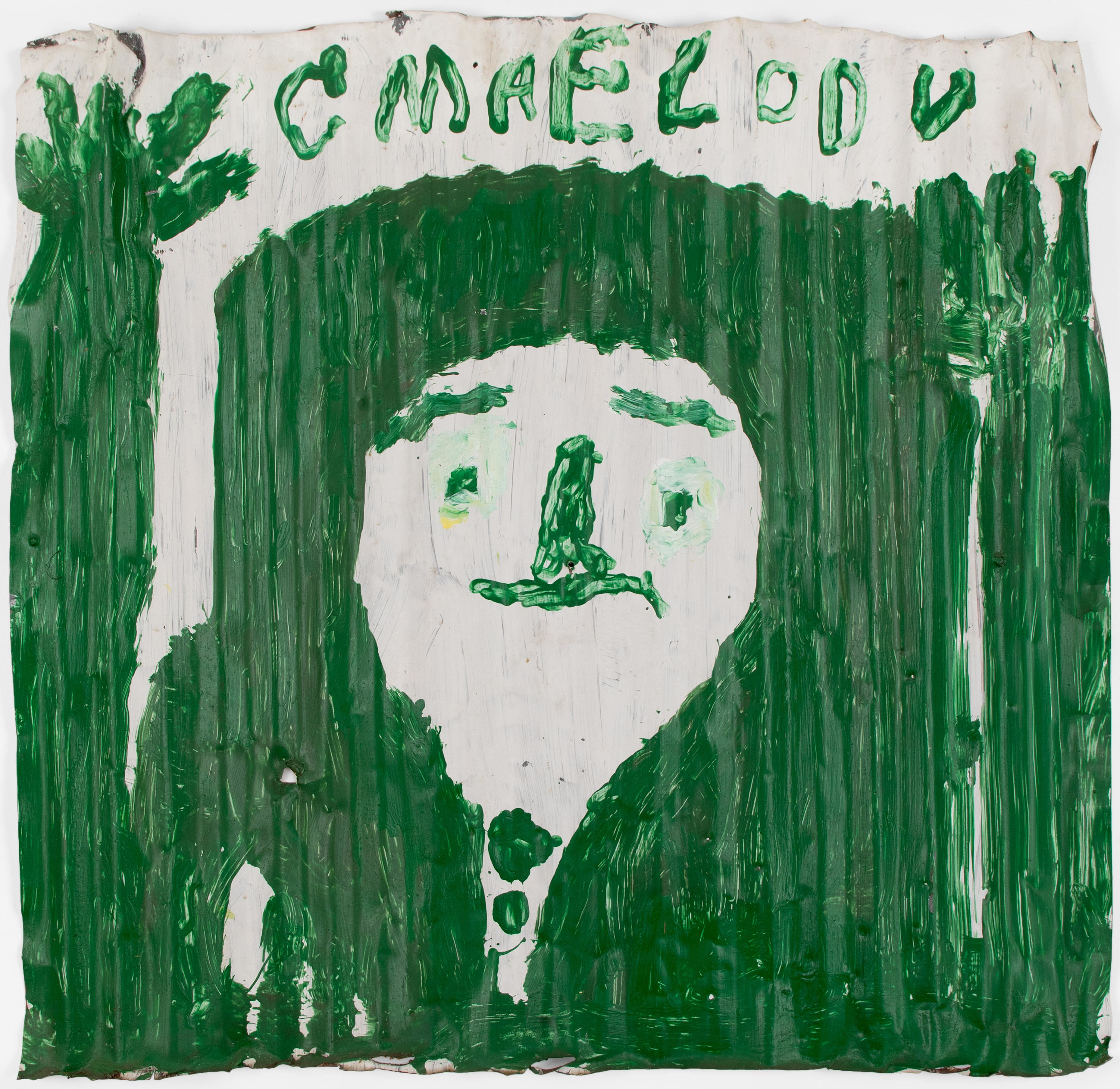

Mary T Smith started out painting Jesus, but before long, the inspiration for her colourful figuration shifted to her family and neighbours in Mississippi. Her house, yard and the makeshift studio she built for herself filled, as the years went by, with portraits, signs and slogans, on tin and board, plus a compelling and cryptic script.

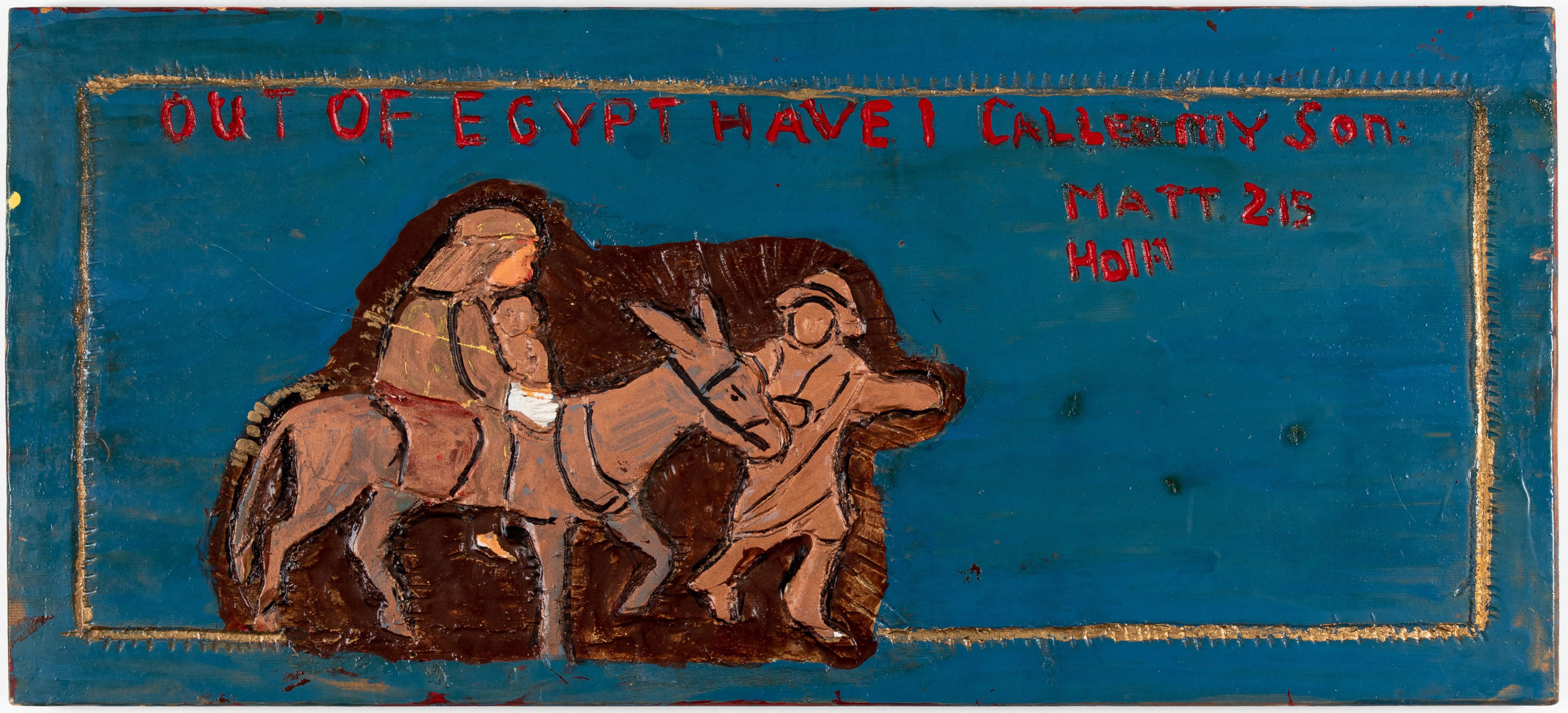

By contrast, Sam Doyle’s paintings on corrugated tin re-imagined both local and popular culture. They comprised an important and dynamic record of the history of the Gullah community of St Helena Island in South Carolina, from portraits of Dr Buzzard, the notorious healer and root doctor, to Doyle's own mother, the island’s first Black midwife, or famous Black sports stars, entertainers, even politicians.

This is a world where fervour abounds. The stocky stick figures of the Reverend JL Hunter comprised a catalogue of gardeners with watering cans, glittering Santas, and sideshow barkers with impossibly long strides. Similarly prolific, the Reverend Josephus Farmer devoted his retirement to bas-relief carvings of negative space and painted banners, which he used as props for his itinerant proselytising.

When we see the work of these artists together, it’s the makeshift qualities that impress. Joy in the texture of rusted metal and rippled wood: of bold bright colours; animistic forms. Scratch a little at this ramshackle veneer, and beneath are intently personal truths. These might be ties to place and local history. They might be a spiritualism, derived from Gospel or from ancestral traditions. They might be American pop icons, seen from an angle you’ve never seen them from before.

Whatever they are – however they first appear – all of this material returns us to the two essential questions it’s worth taking into any encounter with any artwork we ever come across – the questions with which we can ford the illusory river between us and them. What are you saying? And why are you saying it?

Samuel Reilly, 06.07.2023